Here, Queer, Not Going to Disappear: A Retrospective on Drag

“We’re all born naked and the rest is drag” - RuPaul

Drag is defined as the exaggerated performance of femininity or masculinity, traditionally done by a person who identifies as the opposite sex of the persona being performed. In the current cultural debate, drag is often claimed to be a new concept, and it is being perceived as an overt attempt to push other people into queerness. This is decidedly untrue; though drag has only in recent years become a mainstream form of entertainment, it is not a new phenomenon. Drag has a long and complicated history, rooted both in the queerness that it is so heavily associated with and in performance acts completely unrelated to sexuality.

The first instances of drag come from historic theatres. Theatre performances from Ancient Greece to the Edo Period in Japan and through Shakespearean English theatre have used drag performers. In fact, Shakespearean theatre is said to have been where drag earned its name, coming from the dresses of men ‘dragging’ on the floor. In these portrayals, due to a refusal to include women in theatre, men played the female characters themselves, dressing in feminine attire, including dresses, makeup, and wigs. These men are considered to be some of the first drag performers, dressing as women to put on a performance and create a facade of gender falsity. These characters were detached from queerness entirely, and instead found their basis in theatrical performances.

Image: F Yeah History

Molly Houses in 18th-century England, on the other hand, are rooted in queerness and are much closer to what we know drag to be today. They were a place for queer people to congregate, showcasing some of the first ‘modern’ drag performances. In this, they used drag as a form of entertainment amongst themselves. However, these early depictions of drag were often caricatures of gender that more modern drag has tried to move away from. Gay men, who were forcibly associated with hyper-femininity, embraced these stereotypes, playing them up in their performances and mocking female roles with things like mock births. The same can be said for queer women, type-casted as ultra-masculine; they turned the tables when acting as drag kings. These performances of everyday gender norms were so exuberantly enacted that they became unpalatable to the society that imposed these associations on them. Thus, they became a direct rebellion against the society that bound them, as they celebrated who they were.

These theatrical drag performances continued and eventually made their way into the United States through avenues like Vaudeville. Like ancient theatre performances, Vaudeville theatre often included drag performances that were separated from queerness. This style of performance featured a series of short acts, typically including comedy, singing, and dancing. One of the most popular Vaudeville performers was Julian Etlidge. Julian appeared on Broadway, in silent films, and in their exceedingly popular solo act, even performing for the King of England. Julian presented their act in an air of mystery, initially appearing as if they were truly a woman. The crux of their act was the reveal when they would remove their wig and show that they were, in fact, a man. Julian’s act was about the gender of the performer. In this, it was unlike Greek theatre, where drag fit within the narrative. Instead, Julian’s acts were based entirely on gender falsity. His performances were purposefully distant from any queer associations, and he avoided rumors of homosexuality avidly. Still, his performances came to a close as drag began to be associated with queerness, and he faced the subsequent criticism that followed. Vaudeville demonstrates the transition into the drag that we know today, while also existing in a time when drag was not yet explicitly queer. However, the widespread and not unfounded associations with homosexuality had begun, and they would not stop there.

Julien Etlidge

Image: The Legacy Project

In the United States, queerness began to intertwine itself with drag during prohibition. With drinking alcohol being added to the pre-existing list of things to do in the dark, an underground scene of clubs and bars began being utilized more than ever before. As defying prohibition was already in the criminal realm, there was less hesitation to embrace taboo and illegal performances; in this, drag began to shine through the shadows of these clubs and bars. This resulted in a more widespread interest in drag, driven by a kinship found in their defiance. This breakout amongst a larger audience was dubbed “The Pansy Craze.” This craze pushed drag into the spotlight, and though it would be dimmed in ‘cross-dressing’ restrictions, the light would never fully die; drag had established that it was here to stay.

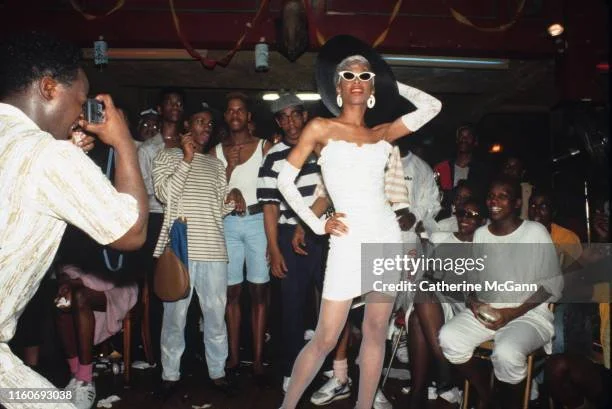

With a love of drag established and prevalent in underground clubs and bars, ballrooms began to take root as an integral piece of the drag scene. Ballrooms were a space where performers could ‘walk’ a runway, presenting their looks and performances to be scored by their peers. These ballrooms, however, were bigger than competition, however, and were often the chosen homes and families of queer people that found little other space in society. It also introduced the concept of ‘drag houses,’ in which people adopted a new and shared last name and performed under these names and with their respective houses. These ‘houses’ were traditionally run by a drag ‘mother’ who acted as a maternal figure for vulnerable queer youth. Ballrooms created a space where, united in their queerness, people found safety and carved out homes away from the eyes of an intolerant society.

Image: Getty Images

Ballrooms were heavily based on beauty pageants, a hyper-heterosexual and overtly feminine event that was then taken and used amongst queer people as another malformation of stereotypes, in and an almost satirical spin of a space queer people were not allowed. As drag became a bigger scene and tolerance started to increase (slowly), drag pageants began to become more mainstream and evolved into a distinct form of drag expression. Pageants were more intensely competitive, and focused more on sharp appearances and fashion than the familial underground ballroom scene. These drag pageants served as a further push both into and against ‘heterosexual’ culture, as they emulated something so traditionally conservative with a queer spin. Pageant culture became much of what drag is perceived to be today, especially as the world transitioned into a RuPaul’s Drag Race-dominated drag scene.

Image: Alt Citizen

RuPaul is one of the most household names in drag, and he extends his reach well beyond the queer community; his name is known to nearly anyone versed in pop culture. Placing himself in New York in the 1980s and 1990s, RuPaul performed in clubs and bars, and he gained popularity as he began producing music. After years of struggling as a drag performer, the release of the hit album Supermodel of the World enabled RuPaul to achieve what queer drag queens had spent decades vying for: mainstream success. He did not stop at one album.; Iinstead, he quickly produced more music and used it in his drag performances, ensuring a spot in queer circles and within a growing heterosexual audience. This upward trajectory continued, and in 2009, he capitalized on it monumentally by starting the reality TV competition show, RuPaul’s Drag Race. The show is now a multi-Emmy-winning franchise, with multiple spin-offs having been created as a result — including Drag Race All-Stars, Secret Celebrity Drag Race, alongside various adaptations in different countries. The show has managed to put drag on a global scale, taking it from underground scenes to international screens.

Not all of RuPaul’s Drag Race’s success and the mainstream rise of drag can be accredited to RuPaul himself; each queen participating on the show has made their mark, propelling the success of the show and, subsequently, the success of drag. The queens on the show exemplify the multifaceted nature of drag, which stems from its complex origins. Queens like Suzie Toot and Jinkx Monsoon channel the intensely theatrical roots of drag, while queens like Bianca Del Rio and Bob the Drag Queen channel Vaudeville-style displays, performing comedy acts on stage while simultaneously being in drag. Some queens attribute their success to the ballroom scene, such as Aja and Olivia Luxx. Meanwhile, pageant queens have won time after time on the show, exemplified by Sasha Colby and Trinity the Tuck. Many of these queens also perform under drag houses, and some are even drag ‘mothers’ themselves — Trinity the Tuck exemplifies this well. In these culminations of styles, the show becomes a living memoir to drag.

The roots of drag dig deep through the centuries, spanning dozens of countries, eras, and various performance styles, cementing itself in many points of history. This counters the current rhetoric that portrays drag as a new agenda to impose queerness onto an unwilling public. Drag is, as it always has been, a performance and a form of personal expression. Despite this, drag is still being restricted through various forms of legislation today. In Montana and Tennessee, there are restrictions against drag performances directly, and legislation in Florida, Arkansas, and Texas all restrict ‘adult performances,’ which have thus overlapped with and disproportionately affected drag. The targeting of drag is not founded on a need to protect, as it is no different from other styles of performance that remain largely unaffected by these legislative changes. Instead, most drag queens and queer people feel that it is a direct attack on their livelihoods and expression that is founded on intolerance.

One of the best ways to combat these perceptions is to support drag queens and the art of drag. Eugene has tried to open their arms to drag, and performances are not impossible to come by if they are searched for. The Haus of Brunch visits various spots in Eugene to perform, while the Barnlight Bar hosts drag events regularly, as does the Cowfish Dance Club and Cafe. For larger appearances, the Hult Center features drag as well — often touring stars from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Specific queens in the area who do rotating shows in various locations are Slutashia, Lyta Blunt, and the drag king Heavy Cream. Drag is a performance, and all performers need an audience.

Cover Image Source: The early history and evolution of modern drag

Embedded Image Sources:

Molly House Image: What were Molly Houses? – The LGBTQ+ history you have to know! – F Yeah History

Julian Etlidge Image: Julian Eltinge | Legacy Project Chicago

Ballroom Image: Drag ball in 1988 in New York City, New York. Pictured: Octavia St.... News Photo - Getty Images

RuPaul Image: Playlist: Sidewalk Strut | Alt Citizen

Sources:

HRC | Understanding Drag: As American as Apple Pie

The history of drag and historical drag queens - BBC Bitesize

What were Molly Houses? – The LGBTQ+ history you have to know! – F Yeah History

https://www.broadwayworld.com/article/What-Was-Vaudeville--A-Brief-History-20240331

How Gay Culture Blossomed During the Roaring Twenties | HISTORY

In the Early 20th Century, America Was Awash in Incredible Queer Nightlife - Atlas Obscura

The History Of Drag Queens And The Evolution Of Drag

Drag Race (franchise) - Wikipedia

Movement Advancement Project | Restrictions on Drag Performances

Instagrams of Mentioned Drag Performers:

Suzie Toot, Jinkx Monsoon , Bianca Del Rio, Bob the Drag Queen, Aja, Olivia Luxx, Sasha Colby, Trinity the Tuck, Slutashia , Lyta Blunt , Heavy Cream

Places to see drag shows in Eugene:

The Haus of Brunch, Cowfish Dance Club and Cafe, Hult Center , The Barnlight Bar