Gorpcore: Gatekeeping the Outdoors

I think I expected Eugene to be hillier when I moved here. Or maybe that at least hiking trails would be easily accessible, even though I’d driven through this part of the I-5 corridor and looked at a map of Oregon enough times to recognize that I now live in the Willamette Valley, which – like most valleys – is flat.

It was common practice for my family to go on walks and critique the new housing developments. Too much stucco, not enough color, three more roof pitches than needed visually and functionally. Once I moved to Eugene, the hills and trails of my walks were gone, but I had a slew of new houses to form an opinion on, and a need to find active outlets that prevented me from going stir crazy cooped up on campus or in dull, boxlike apartments. I found Hendrick’s (the only park with a semi-decent vertical climb) within a couple of days, and it’s become a weekly habit since then. Sometimes I go with music, occasionally with nothing in my ears at all, and, when my brain feels a little more empty than usual, I’ll find a podcast.

Somewhere in early 2024, on an odd three-day weekend where I ran out of vitamin D supplements, the sky was a heavy and incessant grey. After throwing on a hodgepodge of discordant layers, I finally made it out the door and up to Hendrick’s Park. For the first half of the walk, I was flipping through playlists and podcasts – nothing interesting enough to make me forget how cold it was outside and that I had forgotten my gloves. Scrolling back a year in my downloads, I landed on a two-episode series from the podcast 99% Invisible called Trail Mix and then doubled my original walking distance to accommodate the runtime. The first installment covers trail engineering, the Lake District in Cumbria, and the Alltrails app leading hikers astray (worth your time if you have some), but the second part, “Trail Mix: Track Two,” unpacked something I had been noticing all over campus.

Gorpcore (acronym for Good Old Raisins and Peanuts, a.k.a. Trail mix) is a term coined in 2017 to describe the movement of wearing technical outdoor gear for fashion, and not just function. While its popularity in the high fashion world has surged post-COVID (see Bella Hadid, Frank Ocean, and Virgil Abloh), the aesthetic traces its roots all the way back to the Second Industrial Revolution.

Before the 1870s, the outdoors was seen predominantly as a resource, but with the advent of the second industrial revolution, the U.K. and the United States saw the rise of a new leisure class that had the perfect combination of free time and unspent money to transform the outdoors from a logging field to a place for weekend recreation. Coupled with new opportunities to escape city life was the development of large-scale garment manufacturing starting around the U.S. Civil War. Army uniforms introduced not only sizing standards, but also the need for clothing materials engineered for element exposure and wear over time. The manufacturing and recreation worlds met in the early 1900s, when Abercrombie and Fitch built their camping goods/clubhouse in the heart of Brooklyn, New York. The interior was marked by excessive taxidermy and a “Log Cabin Lounge” to recreate a mountain getaway in New York’s claustrophobic city experience.

The upper-middle-class American people were attempting to cosplay a rugged outdoor life. Where buck skin suits were once hand-made out of necessity for their durability in nature, they were now bought from Indigenous women (as was done by Theodore Roosevelt) to masquerade as experienced outdoorsmen.

But there was still some element of everyday practicality left in the rapidly expanding outdoor wear industry. The birth of the L.L. Bean Boot in 1912 laid the groundwork for water-resistant hiking footwear, and synthetic fabrics (synthetic rubber, neoprene, etc) made by DuPont throughout the 20s, 30s, and 40s allowed consumers to maintain their fashion, but not at the expense of their comfort. World War II further propelled advancement in the creation of tactical outdoor gear and garments, but when the war was over, there was excess gear with no soldiers to wear it. This overstock fed directly into the Military Surplus Stores that bloomed post-1945. Camping and hunting goods were now widely accessible at a lower price point in the US. Progress continued as Gore-Tex was created (a material that allows sweat to go out without letting water in), and gear got better. It wasn’t until the 1980s and 90s that outdoor wear became fashion mainstream, first with The Preppy Handbook, which popularized Eddie Bauer’s and L.L. Bean’s puffer vest-centric looks, and then again in 1994 when Raekwon of the Wu-Tang Clan wore a Ralph Lauren ski jacket, signaling the integration of outdoor wear and streetwear.

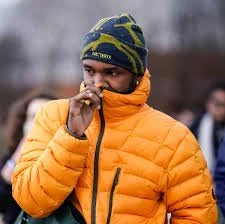

By 2015, Gorpcore had found its footing in the high fashion world. The September issue of Vogue pairs Sorel snow boots with Valentino and Alexander McQueen, bridging the worlds of function and fashion and lending a sense of legitimacy and utility to high fashion in the process. This was followed by Arc’teryx jackets showing up at the front row of fashion week runways, Solomon shoes in urban Austin, carabiners to hold car keys, and a stray Miffy trinket, and then the Gucci x North Face collab in early 2020. Gorpcore had woven its way into the everyday outfits of every consumer, no matter what price point they bought at. All this outdoor gear proved itself in a new way when COVID hit, and households found themselves spending time in nature that would normally be spent gathering indoors with others.

Gorpcore still finds novelty in promoting the sense of “investment dressing.” “We’re going to take this concept that’s associated with utility, with usefulness, with practicality, also with this sort of privilege of being able to get out and about in a certain way,” says Jessica Glasscock, an adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design. Arc’teryx jackets still run $300 plus, Solomon GTX shoes are roughly $200, and the titanium water bottle from the brand Snow Peak featured as the singer Lorde’s current profile pic on Instagram is $140 without shipping. These price tags may be lofty to the everyday buyer, but these goods are also built for the activities we do every day, whether that be walking a dog in the rain or going on a walk during a boring weekend in Eugene, and they are built to last. It’s still a wealth show to an extent, but 99% Invisible podcast correspondent Avery Trufelman suggests something a bit simpler: “Gorpcore works.”

Sources:

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/trail-mix-track-two/

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-america-gorpcore-fashion-history/?embedded-checkout=true

https://articlesofinterest.substack.com/p/gear-chapter-1

https://www.outsideonline.com/culture/essays-culture/outdoors-high-fashion/

https://www.reddit.com/r/camping/comments/ajr5lk/when_did_it_become_camping/